Tagged: international booker prize

Hunchback by Saou Ichikawa, translated by Polly Barton

In keeping with the spirit of this book, I will be brief.

Shaka is a wealthy middle aged woman with disabilities who lives in an assisted care facility. She says the following about holding a heavy book:

Holding in both hands an open book three or four centimetres in thickness took a greater toll on my back than any other activity. Being able to see; being able to hold a book; being able to turn its pages; being able to maintain a reading posture; being able to go to a bookshop to buy a book—I loathed the exclusionary machismo of book culture that demanded that its participants meet these five criteria of able-bodiedness. I loathed, too, the ignorant arrogance of all those self-professed book-lovers so oblivious to their privilege.

I found it ironic that many reviewers criticize the book for being too short, with underdeveloped characters and plot. To be fair, Hunchback is extra short, stretched over 90 pages in my edition due to wide margins and small pages. But I thought it was clever to have the form follow the spirit of Shaka’s complaint.

Ichikawa packs a ton into those pages – a frame narrative, excerpts from Shaka’s erotic fiction and tweets, literary allusions, some Covid commentary, and yes, a plot – a pretty shocking one!

The frame narrative stars Mikio, a persona Shaka uses to write erotic fiction, which we get to sample in the first few pages. At the end of the book, Mikio reappears and upends everything, in a way that I of course cannot describe here.

Shaka’s story, within this frame, is encapsulated in this anonymous tweet:

My ultimate dream is to get pregnant and have an abortion, just like a normal woman.

Shaka’s not serious at first – it’s more of a provocative commentary on rights for people with disabilities. But when she starts to act on this impulse, Hunchback becomes a story about class as well as disability. She finds a poor “beta male” who works in the assisted living facility to make her dream into reality.

And here’s where I had a little trouble. The scenario is a little far-fetched. The author has said that about 30 percent of Hunchback is based on her life. She asks the reader to believe a lot of convenient things, presumably the fictional 70 percent, to drive the plot and give it symbolic weight.

What ensues is a very twisted Normal People scenario in which a rich girl alternately wants to submit to, and assert her power over, a poor boy who is sort of her employee (this boy is no Connell though, alas). If Ichikawa appeased the critics and developed the story further into the future, or delved into Shaka’s past, it could have become even more artificial. As it stands, the somewhat-convenient plot is balanced by the strength of the writing and the astonishing ending.

The International Booker Prize jury found something compelling in short narratives this year. With the exception of Solenoid, each longisted book is under 300 pages, and most are under 200. Hunchback is not underdeveloped at all. The length works, thematically and structurally.

If I have a criticism, it’s that the narrator’s erotica and shitposts are pretty tame, and I’m not sure if that was intentional or not. But that might say more about my reading and scrolling habits than anything!

On the Calculation of Volume I by Solvej Balle, translated by Barbara Haveland

On the Calculation of Volume I is a compelling read, which is impressive, given that very little happens, and the end of the book is not the end of the story. It’s the beginning of a planned septology, and the last two or three books haven’t even been written yet.

Like The Unworthy, this is a novel written as a diary of a woman who is going through something strange, but unlike The Unworthy, that point of view is perfectly executed. You get the sense that the author has a bigger purpose, a structure that isn’t obvious yet, that needs to be played out in seven parts. I hope it’ll come together just like the calculation of volume came to Archimedes. Just know that there is no “Eureka!” moment in this first book.

Before we talk about what this narrator is going through, I recommend you read this review, in The Cut of all places, which provides some important background on how this book came to be. If you are, like me, annoyed by ambiguous timelines and convenient ways of circumventing technology, it’s helpful to know that Solvej “conceived of On the Calculation’s concept in 1987, then started writing in 1999.” I learned this after finishing the novel, and was instantly less annoyed by the fact that the narrator doesn’t try to use technology to figure out what’s happening to her. If there ever was a time to google “[problem] + reddit”, this is it…

The problem is that, as the story opens, Tara Selter has been living the same day, November 18th, over and over again, 121 times and counting, while the rest of the world is seemingly reset overnight and experiencing a normal, one-and-done day. Her diary takes us back to the first November 18th, the one that was preceded by November 17th, then through some of the intervening 120 November 18ths, and then forward through an entire year of them, without making the diary device feel forced or artificial.

Most of the book is given over to the practical problems of existing out of time, of which there are many. How many times can Tara explain her problem to her husband in the morning, get his help and advice through the day, just to wake up and have to explain it all over again? How long can she hide out in her own house, or other houses, to avoid him when it becomes clear that he’s holding her back? How much food can she eat before the empty cupboards in the house, and then the store shelves in town, are noted? How closely can she observe the world for deviations in how the day unfolds, whether in the movement of stars, or the way a person in a Paris hotel drops a piece of bread at the same time every day, and will those deviations lead her to a way out of November 18th, and back to the regular passing of time?

The most magical thing this book does is make one wonder who has it worse: Tara, stuck in one day, with no way to have a relationship with anyone or anything that lasts more than 24 hours; or everyone else, moving through their November 18th like automatons, unable to exercise free will or see beyond the ruts they run in. Only Tara can step back and try new routes and new angles, and see the possibilities that exist in one day.

One missing element did annoy me though. I kept wondering whether or not Tara gets periods or if she could get pregnant. Hubby’s always willing, no matter what iteration of November 18th we’re in or how far they get in their time travel investigations, and no birth control is mentioned. Other bodily functions seem to move forward, even though the days don’t. Nothing snaps a woman in line with time and seasons and cycles more than all that. But in addition to not knowing what year it is, we also don’t know how old Tara is, so I don’t really know how much of a factor this could be.

I guess we have six more books in which to figure that out, along with more pressing questions like why did this happen to Tara and how can she break free? I look forward to shouting “Eureka!” in a few years, once those last books are written and translated into English – assuming I don’t fall into a time warp before then.

How to read the 2025 International Booker longlist in Canada

Like last year, the 2025 International Booker Prize longlist is out of left field. Former winners, who I thought were a lock, were shut out (Han Kang, Olga Tokarczuk, László Krasznahorkai) and some of these translations were published in North America before the UK, which is unusual. But the most surprising thing about this longlist is that every author is an IBP first-timer. Past longlisters like Yoko Ogawa were shut out too.

I have to think this was on purpose, and I’m not sure how I feel about it. Does Han Kang need this, months after winning the Nobel? Surely not. Is each of these 13 books better than her latest, We Do Not Part, which I read because I was so certain it would be longlisted? Highly unlikely.

2025’s longlist is diverse, representing ten original languages and eleven nationalities. There are a couple of short story collections, several novellas (the shortest of which is practically a short story itself at 112 pages,) and one near-700 page chunkster. The list is skewed towards women (9 of 13) and boomers (6 of 13), and trends a bit older in general. There is no Gen Z representation at all, and the millennials are of the elder variety.

Find these stats and everything you need to know about obtaining these books in Canada in the updated “How to read the IBP in Canada” spreadsheet, or if you’re in a hurry, you can refer to the plain-text longlist below.

The longlist is fairly accessible in Canada. By the end of March, all the books will be available from Blackwell’s for the bargain price of $337.23 CAD. If you prefer to spend your money locally (elbows up and all that) most of them will be available through Canadian retailers too, with the exception of Small Boat and There’s A Monster Behind the Door. I’m just disappointed that my library system has none of these in ebook format. If Kobo thinks I’m going to spend $25.99 on a 192-page ebook (Eurotrash), they’ve got another thing coming.

I don’t quite know what to make of the longlist, but I’ve already read one (On the Calculation of Volume I, the first in a septology, but not the first partial septology to be longlisted!) and have another seven on the way, either from Blackwells, Magpie Books, or the library. In the meantime, the IBP Shadow Panel has created a Substack to round up their reviews. They are without their usual leader, Tony from Tony’s Reading List – he’s still blogging though, so if you want to see what’s going on in translated lit outside of this list, he’s your guy.

If you want to know my thoughts, well, let’s see if I can crank out a few reviews. First challenge: say something about On the Calculation of Volume, a story about a woman who wakes up to the same day over and over again, without mentioning Groundhog Day.

- The Book of Disappearance by Ibtisam Azem, translated from the Arabic by Sinan Antoon

- On the Calculation of Volume I by Solvej Balle, translated from the Danish by Barbara J. Haveland

- There’s a Monster Behind the Door by Gaëlle Bélem, translated from the French by Karen Fleetwood and Laëtitia Saint-Loubert

- Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu, translated from the Romanian by Sean Cotter

- Reservoir Bitches by Dahlia de la Cerda, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary and Julia Sanches

- Small Boat by Vincent Delecroix, translated from the French by Helen Stevenson

- Hunchback by Saou Ichikawa, translated from the Japanese by Polly Barton

- Under the Eye of the Big Bird by Under the Eye of the Big Bird, translated from the Japanese by Asa Yoneda

- Eurotrash by Christian Kracht, translated from the German by Daniel Bowles

- Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico, translated from the Italian by Sophie Hughes

- Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq, translated from the Kannada by Deepa Bhasthi

- On a Woman’s Madness by Astrid Roemer, translated from the Dutch by Lucy Scott

- A Leopard-Skin Hat by Anne Serre, translated from the French by Mark Hutchinson

How to read the 2024 International Booker Prize longlist in Canada

My International Booker predictions were a bust, again! Not that I committed them to paper (or blog,) but I was very much expecting to see My Heavenly Favourite by previous winner Lucas Rijneveld, and was hoping to see some Japanese lit after a shut out last year. No such luck.

2024’s longlist is South America and Europe heavy, with a single Korean novel representing Asia. Africa and the Caribbean are shut out entirely. There are no French language novels, a first since I’ve been tracking.

I’m not sure what I expected from this jury, headed up by one of my favourite radio personalities, Eleanor Wachtel, but this wasn’t it. Apart from Jenny Erpenbeck, these are all totally new-to-me authors, so maybe I’ll find a find a new favourite, heavenly or otherwise…

Now, the reason you’re here: the updated “How to read the IBP in Canada” spreadsheet. Check it out for all the details on where to get the books in Canada (and the States – but prices are in CAD). The longlist is fairly accessible, if you’re looking to buy, and about half are available at my library (shout out to the two people who got holds in ahead of me on all seven available titles! I was slow on the draw). There’s not much in the way of audio, and the ebooks are a bit pricey, but overall, us Canadians can get a good start on things ahead of the shortlist announcement on April 9.

Continue readingInternational Booker Prize 2023 mini reviews

Here are my brief thoughts on the books I’ve read so far, and my plans heading into the home stretch. It’s been nice to get back into the IBP this year, after a half-hearted 2022, skipping 2021 entirely, and getting derailed after a strong start in March of 2020. Not all the books have been nice though!

A System So Magnificent It Is Blinding by Amanda Svensson, translated from the Swedish by Nichola Smalley

This book is trying to be so many things, but ends up being a big old mess. I saw a reviewer compare Svensson to Franzen and yes, there are some similar themes around family, activism, and shadowy bureaucracy, but that’s not all there is to this book. Svennson adds: triplets! Babies switched at birth! Possible incest! Suicide! Cults! Monkeys! Infidelity! Depression! Eating disorders! Synesthesia! Child actresses! Peacock feathers! I’m sure I missed several recurring themes. All this stuff took attention away from the main family unit, which, Franzen would never.

Pyre by Perumal Murugan, translated from the Tamil by Aniruddhan Vasudevan

I said what I needed to say in this post. This story was too opaque for me, so I felt a remove, but I would try more from the author, particularly The Story of a Goat.

The Birthday Party by Laurent Mauvignier, translated from the French by Daniel Levin Becker

People talk about this book like it’s a thriller but it’s a lot more… but also a lot less. More because of the complex language and extremely close narration, and less because when the story finally tips over from expectation and dread to action, it kind of falls apart. The meandering style works very well for revealing shocking parts of the character’s thought process and history, but a lot less well for shocking violence and split-second decisions. Then, the ending left me with more questions than answers, and not in a good way.

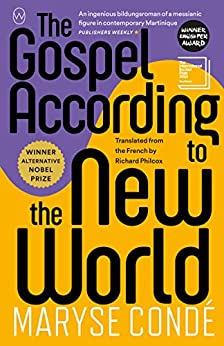

The Gospel According to the New World by Maryse Condé, translated from the French by Richard Philcox

I was hyped for this book because I’ve enjoyed both Caribbean literature and Bible retellings in the past. Then I read some reviews that said this was too close of a retelling, with not much new to say. That might be true, but, I loved it. At times funny and absurd, it was mostly just calming and meditative. Reading this felt like a respite from life. Which is sort of how my religious grandparents would talk about their faith, so, there’s that! Condé is a fascinating person, and I wish I could find an English translation of her Wuthering Heights retelling (which is the equivalent of the Bible for me).

On deck, I have copies of Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth, translated from the Norwegian by Charlotte Barslund, and Time Shelter by Georgi Gospodinov, translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel out from the library. Is Mother Dead didn’t make the shortlist, but it’s a shorter (and beautiful, with full colour endpapers) book so I will try to get through it. I’ve read a few raves about Time Shelter. My copy of Boulder by Eva Baltasar, translated from the Catalan by Julia Sanches finally arrived, and I’m waiting on Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan, translated from the Korean by Chi-Young Kim… and that’ll do it for me, unless something not listed here takes the prize, as I always like to read the winner!

How to read the 2023 International Booker Prize longlist in Canada

2023 will go down as the year everyone’s International Booker Prize predictions were wrong. I was surprised not to see Mieko Kawakami, Han Kang, Yōko Tawada, or Sayaka Murata, and I was so sure we’d see the new Can Xue, Barefoot Doctor, that I shelled out nearly $30 for the ebook!

I love this list though. It’s the most accessible one I’ve seen in years, meaning that even in Canada, you can read the whole longlist ahead of the prize being awarded, if you want to. You could buy half the longlist right now from Canadian retailers. You could buy the whole longlist from Blackwell’s for $332.77 CAD.

These insights and more are available in my annual spreadsheet. It includes a bit of demographic info, but mostly helps you figure out where to obtain these books in Canada for the best price. My sources are noted, but generally, Canadian cover prices are from Glass Bookshop, library availability refers to Edmonton Public Library, and UK editions are from Blackwell’s. All prices are in CAD and include shipping. I didn’t bother linking to publisher’s websites this time, because for once, it’s not necessary.

I’m happy to see a nice range of languages (Tamil, Bulgarian, Catalan, and Norwegian, in addition to the usual suspects – but notably, no Japanese!) and a nice range of ages (the youngest writer is 35-year-old Amanda Svensson, while the oldest, and the oldest ever to make the list, is 89-year-old Maryse Condé – or is she 86, as Wikipedia claims?) though it’s skewing a little older this year, and very heavy on Gen X writers (seven out of 13).

I got a lot of traction (i.e. almost 100 likes) on a tweet complaining about the “creative” way book prizes present their longlists. The International Booker Prize gave us the courtesy of a text-based list, but even then, you have to click through to see the authors and translator names, so for your convenience, here’s your plain-text, detailed longlist*:

- Ninth Building by Zou Jingzhi, translated from the Chinese by Jeremy Tiang

- A System So Magnificent It Is Blinding by Amanda Svensson, translated from the Swedish by Nichola Smalley

- Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel, translated from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey

- Pyre by Perumal Murugan, translated from the Tamil by Aniruddhan Vasudevan

- While We Were Dreaming by Clemens Meyer, translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire

- The Birthday Party by Laurent Mauvignier, translated from the French by Daniel Levin Becker

- Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv by Andrey Kurkov, translated from the Russian by Reuben Woolley

- Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth, translated from the Norwegian by Charlotte Barslund

- Standing Heavy by GauZ’, translated from the French by Frank Wynne

- Time Shelter by Georgi Gospodinov, translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel

- The Gospel According to the New World by Maryse Condé, translated from the French by Richard Philcox

- Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan, translated from the Korean by Chi-Young Kim

- Boulder by Eva Baltasar, translated from the Catalan by Julia Sanches

And shout out to Bookstagrammer time4reading who posted her own simple list of books plus where to source them in Canada – she’s Toronto-based, so if your library or prefered bookstore is in TO, check her out.

As always, follow the IBP Shadow Panel for reviews and Eric Karl Anderson for a peek behind the scenes (he usually gets to go to the awards ceremony, I think!)

*Not seeing any official sources for the original languages so I took my best guess!

How to read the 2022 International Booker Prize longlist in Canada

In what has become a biennial tradition (see 2018, 2020), I present to you my guide to the International Booker Prize for Canadians. The fact that this is necessary is a good thing, as it means this prize continues to spotlight small publishers. Small publishers don’t always have international distribution, but, where there’s a will, and a spreadsheet, there’s a way.

Continue readingFaces on the Tip of My Tongue by Emmanuelle Pagano – International Booker Prize review

The story of how Emmanuelle Pagano’s 340-page French short story collection, Un renard à mains nues, became the 128-page International Booker Prize nominated English collection Faces on the Tip of My Tongue is almost as interesting as the stories themselves. Peirene Press, the English publisher, exclusively offers books that can be read “in the same time it takes to watch a film,” so Un renard needed to be drastically shortened. Translators Sophie Lewis and Jennifer Higgins narrowed down the stories to those that best conveyed the themes, then divvied them up, translating alone before trading drafts back and forth and critiquing each other’s work.

The result is a charming, disorienting, tightly connected collection that literally does something that many a novel tries to metaphorically do: forces the reader to consider different perspectives.

Continue readingHow to read the 2020 International Booker Prize longlist in Canada

Once again, I have rashly decided to follow the International Booker Prize. I learned some harsh lessons in 2018 about how difficult it is to get new and obscure UK books in Canada, and I’m back to share my wisdom (and spreadsheet) with you.

This year’s longlist looks a bit easier to manage than the 2018 edition. I found at least one way to access each book in Canada. I was able to start Faces on the Tip of my Tongue immediately on my Kindle, for the low price of $5.59, and I will use an Audible credit for one of the three audio titles available, perhaps starting with the The Memory Police, which appears to be the most straightforward plot (that’s saying something, given TMP’s surreal premise.)

If you’re in Canada, take a peek at my spreadsheet for a variety of options, including bookstore cover prices, plus ebook, audio, and international ordering. For books that aren’t published yet, I noted the publication dates, though hopefully some will change – one book isn’t published here until September!

A few other things to note:

- I didn’t include library options here as it will vary by system, but always check the library first! In my library, two titles are on order and one is available but waitlisted. See if you can request titles that aren’t in your library’s catalog.

- I took my cover prices from Amazon and Chapters, but you should of course avail yourself of your favourite local indie bookstore.

- I included Blackwell’s as my international ordering option because I’m not a fan of Book Depository, but it’s probably safe to assume anything at Blackwell’s is available there too.

- Direct-from-publisher prices were converted to CAD by me, your credit card company may have different ideas.

- Feel free to make a copy of my sheet and use it to track your progress.

- I am not responsible for any TBR explosions or book budget overruns that may result from irresponsible use of this spreadsheet.

Canadians, and Americans of North, Central, or South varieties: are you reading the IBP this year? How are you getting your books?