Tagged: CanLit

20 Books of Summer 2025

A refreshed 20 Books of Summer challenge is upon us! Unlike last year, I do have 20 books to choose from, but it’s more realistic for me to commit to ten. My most successful 20 Books of Summer was my first, in 2019, when I read and reviewed 14 books, but I’ve never come close to that again. I join this challenge as an intention: to read these books (eventually) and to spend time writing reviews during the summer.

This year, new hosts have taken over for Cathy. I for one welcome our new overlords, AnnaBookBel and Words and Peace.

My list is another random assortment of books in my house or that could be in my house soon:

- Less by Andrew Sean Greer (cheating because I’m halfway through it now)

- The Netanyahus by Joshua Cohen (carry over from last year)

- Athena by John Banville (the last in the Book of Evidence series)

- Small Boat by Vincent Delacroix tr. Helen Stevenson (an IBP shortlister)

- There’s a Monster Behind the Door by Gaëlle Bélem tr. Karen Fleetwood and Laëtitia Saint-Loubert (an IBP longlister)

- Playing Hard by Peter Unwin (a review copy, a collection of essays about games and sports)

- Don Quixote by Cervantes tr. Edith Grossman (I thought about doing a read along but I’m too lazy)

- Mornings Without Mii by Mayumi Inaba tr. Ginny Tapley Takemori (cover buy!)

- Yoga by Emmanuel Carrère tr. John Lambert (been on my TBR since I read this review)

- On the Calculation of Volume II by Solvej Balle tr. Barbara Haveland (next in the septology)

Join in and let’s review some books! I promise to comment on yours if you promise to comment on mine.

Bad Land by Corinna Chong

I don’t love the mountains, which is a controversial thing to say here in Alberta. Everyone goes to the mountains, and feels at peace, at home, in awe, or whatever. Many “leave their heart” there. Maybe it’s because I grew up in Vancouver, where it was normal to see mountains (and an ocean) but I need a little more than a large rock formation to get me speaking in clichés.

I’m also not easily impressed by so-called disaster woman stories. There’s got to be a little more going on than “this woman is weird and messy.”

Bad Land, thankfully, has got more going for it. In addition to a weird woman, there is also a weird little girl. And it’s not set in the mountains; it’s set in the one place in Alberta that actually does make me feel a sense of awe: the badlands.

“Then the puckered hills begin to swell out of the earth, growing higher, wider, baring their stripes of ancient rock and clay and ash, layer upon layer. As the Buick sinks into the valley, the hills knit together behind them, closing them in.”

That’s exactly how I feel driving into Drumheller. The landscape is not just majestic and imposing, it’s downright alien. It also contains a ton of fossils and other buried treasures, enough to capture any child’s imagination.

Growing up there makes it a little less magical. Regina’s Drumheller childhood with her younger brother Ricky and German paleontologist mother, called “Mutti,” feels as stifling as you might expect. The book opens with adult Regina still there, living alone in her childhood home, estranged from her family, and working at the most stereotypically Drumheller place possible. She’s a character, known for taking her beloved bunny, Waldo, for walks around the neighbourhood, and for her imposing size. Regina is surprised to find Ricky on her doorstep after seven years of no contact, with a six-year-old daughter, Jez, in tow. The rest of the novel unravels the reasons for the estrangement, and tracks Regina’s bond with troubled Jez and her efforts to find and reconcile with Mutti.

A flashback illustrates Regina’s strained relationship with her mother. Young Regina tries to impress her mother by finding treasures in the badlands, thinking that Mutti would “gasp, praise my keen eye, and offer to take me out for ice cream” if she could just find a fossil, or a piece of amber. Regina eventually finds what she imagines is a dinosaur egg. When she breaks it open with a hammer and finds something even more magical – sparkling crystals – she imagines Mutti will “jump out of her stockings” and that they will be famous for their discovery. Of course, it’s just a geode, and Mutti is quick to tell her it’s nothing special, at least not anymore.

“It might have been worth something, you know. I think about four hundred dollars, maybe more. But there you’ve gone, smashing it to bits. Must you go around smashing everything, Regina?”

Chong has dug into strained mother-daughter relationships before, in her debut novel Belinda’s Rings. Both novels feature distant mothers with the kind of STEM jobs that little girls dream about (a marine biologist in Belinda’s Rings), absent fathers, fraught sibling relationships, and generational trauma and abuse. Sudden outbursts of violence feature in both books. The past is always just below the surface, threatening to break through. Bad Land is a more mature work, and takes more risks. It can be read as a thriller, full of twists and family secrets, culminating in a madcap road trip. Or, it can be read as an examination of one woman’s inner life, rich in metaphor and atmosphere, and mysterious in its conclusions about family and memory.

Maddeningly for such a propulsive read, Chong makes some choices that throw the reader out of the story. The most jarring was Regina’s analog lifestyle – no phone, no computer, and as far as we’re told, no media consumption at all. I was compelled to hunt for clues about her age and the year, hoping to justify this choice as something other than a plot contrivance – as with most fiction, it’s very helpful when characters can’t Google things- but Bad Land is mostly devoid of political and pop culture references. I eventually found enough to place the present-day narrative in 2016, and peg Regina at 36, which makes Regina’s inability to conduct a simple Google search strain credulity.

I flew through Bad Land, but upon finishing, I wasn’t sure how I felt, or how successful the novel was. So, I sought out reviews. Surely, a Giller Prize-nominated novel that was published mere weeks ago would have a couple of reviews to peruse. Other than an unfairly negative review in Publisher’s Weekly (which refers to Randy’s wife as Clara rather than Carla) and a positive review in a BC literary journal (which refers to Waldo as a childhood pet; he’s definitely not) there’s very little to go on. There are ten reviews on Goodreads, one of which is mine. This probably says more about the state of review culture than the book, but I was sorely disappointed!

Despite my uncertainty, I hope more people read Bad Land, mostly so I can read more perspectives on it. I want to know whether you think Regina’s character is supposed to reflect how childhood trauma becomes an adult fear of abandonment, and that her bond with Jez shows how trauma can be healed by the love of a child. Or, as I tend to think, that Regina is the “bunny lady” and Jez is lost in a dream world for reasons that aren’t so simple, or maybe for no reason at all.

Like a fossil is only an impression of the real thing, all we can know of Regina is what Chong shows us. Bad Land is haunting no matter which way you read it – and like a geode, whether you break it open the right way or not, it’s still beautiful.

My Year of Last Things

This is a book blog, not a personal blog, but I do write about life events here, and sometimes things don’t feel real until I do.

The births of my children are here. Moving into our house, briefly. My sister moving to the States. Then the fire happened, and I wrote about what it’s like to lose all your books, but I didn’t write about what it’s like to lose a pet.

If you follow me on social media, you might know that in the immediate aftermath of the fire, my husband found our cat Perogy in a bad state and got her to an emergency vet, where she remained for three weeks. You might have missed the “Missing Cat” posts about Shirley, though, as they were only up for a day, until my husband found her too. She didn’t make it.

Shirley was three years old, a pandemic pet born in 2020 and adopted by us in 2021. The SPCA named her and we didn’t see any reason to change it. She was loud, lazy, a bit of a glutton, cuddly, soft, playful, a constant companion to anyone sitting on a couch or lying in a bed, and scared of everything. She would have been very scared that day – the noise, the smoke, the heat, people stomping around. The firefighters told me she most likely escaped the house and we’d find her later, that it happens all the time, but I didn’t believe them.

I’ve never lost a pet this way, only older pets who were ready to go and gave us time to prepare. I’ve also never lost a pet in the midst of a crisis – usually losing the pet is the crisis. I have mourned her, but alongside a bunch of other stuff, and seven months later, it can still feel awfully fresh; never more so than when I read the poem “November” in Michael Ondaajte’s new collection A Year of Last Things.

I’ve tried Ondaatje’s poetry before, and found it fairly impenetrable, with literary and cultural references that are beyond me. A lot of the poems in this collection are like that, though I got a hint of something different in this first line of the first poem, “Lock”:

Reading the lines he loves

he slips them into a pocket,

wishes to die with his clothes

full of torn-free stanzas

and the telephone numbers

of his children in far cities

I love that line about carrying the telephone numbers of your children in your pocket. Old fashioned but relatable. Later, we are treated to prose poems – mini-essays, really- about the horrors of boarding school and confronting an abuser.

And then there’s “November“:

Where is my dear sixteen-year-old cat

I wish to carry upstairs in my arms

looking up at me and thinking

be careful, dear human

Ondaatje addresses his cat, Jack, and remembers how he was adopted (“I found you as if an urchin in a snowstorm”), how he became a member of the family, (“learned the territories of the house”) and grew old (“Was it too soon or too late/that last summer of your life”). He despairs that he “cannot stand it,” this loss, and imagines meeting Jack again in a place “where language no longer exists”.

This poem has nothing much to say about my particular circumstances. “November” is about an old cat, and an old owner who can imagine meeting him again soon. Shirley was a young cat, and I am a (relatively) young owner who, if I believed in an afterlife, would anticipate waiting a long time for such a reunion. This poem doesn’t have anything particularly new to say about grief, either: it ends in a paraphrase of a 17th century haiku about the timelessness of nature, maybe, or the endless nature of grief?

It’s not a good poem because of what it says, but because of how it says it. It’s good because in ten stanzas (read them all here), it reminded me that my grief is real, and made me write about it here, making it even more real. It’s good because it made me think about my brother, who imagines his cat referring to people as “humans,” usually derogatory, and that made me smile. It’s good because the line near the end, “You no longer wait for us” took my breath away. Cats aren’t loyal and protective like dogs, but they do wait for you. I think about Shirley waiting for me that day. I knew she didn’t leave the house. She waited where she always did when she was scared, under the couch. That couch was just too close to the fire.

This is barely a review but it does remind me, and hopefully you, why it’s a good idea to read poetry: for those lines that takes you back to a place or a feeling, even one you cannot stand going back to.

Shirley, lying on top of someone’s legs as they lounged on the couch, as she was wont to do

20 Books of Summer 2024

20 Books of Summer has always been more about the motivation to *actually review* books for me, not reducing my TBR, and never more so than this year. I don’t own 20 books, let alone 20 books I haven’t read before. Hence the shorter list.

This year is special though, as it’s the tenth anniversary of an event that started as a TBR challenge with 8 participants that now attracts upwards of 100 bloggers each year. No mean feat given the state of blogging today and the fact that this is a rather high-commitment event (with very relaxed rules to make it manageable.) Congratulations to Cathy for keeping the pages turning and the reviews rolling in since 2014.

My list of 15 has no theme other than “these are books in my house or that I might get into my house at some point this summer”:

- Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami tr. Sam Bett and David Boyd (for Women in Translation month, perhaps)

- The Wars by Timothy Findley (a CanLit classic)

- A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith (an American classic)

- The Netanyahus by Joshua Cohen (has been recommended to me many a time)

- Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë (the book I was rereading at the time of our house fire, apologies to Edmonton Public Library for the lost copy!)

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (it’s in the edition I got in order to read Agnes)

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (see above and it’s time for a reread anyway)

- Ghosts by John Banville (the next in the Book of Evidence series)

- Brooklyn by Colm Tóibín (a rare instance of “seen the movie, not read the book” and preparation for…)

- Long Island by Colm Tóibín (the much-anticipated sequel)

- Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck tr. Michael Hofmann (my tradition of reading the International Booker Prize winners continues)

- Laser Quit Smoking Massage by Cole Nowicki (a slim essay collection)

- A Year of Last Things by Michael Ondaatje (a slim poetry collection)

- When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön (they sure have been)

- The Tenderness of Wolves by Stef Penney (a Little Free Library pick)

Join in and let’s get this TBR back down to zero, or at least review some books this summer!

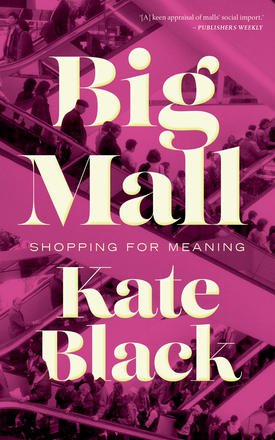

Big Mall by Kate Black: Review + Author Q&A

I’ve lived within a 15-minute drive of West Edmonton Mall for more than thirty years. With 800+ stores as a backdrop, I grew from a teenage mallrat to a mom doing the back-to-school shopping. I had my first kiss in a photo booth near the mini golf course, and shopped for a wedding dress in the wedding district (upstairs, Phase I) 15 years later. In 2002, I watched Canada win gold* on a TV in Vision Electronics while on a break from my job in Galaxyland (formerly Fantasyland, long story) and in peak 2022 fashion, I got stuck inside a drugstore during a lockdown drill while waiting for a COVID shot.

Still, I sometimes forget that this is what Edmonton is known for. Not Oilers hockey, not the river valley, not the time we tried to make “Take a risk, it’s the most Edmonton thing you can do” happen, but a building that we just call “the mall.” It makes me think: Really? Her?

Big Mall is a deeply researched and deeply personal book that says yes, her. Kate Black breaks down why malls exist in the first place, how they proliferated, why they’re dying, and what it all means, through the lens of someone who grew up in the shadow of the world’s one-time biggest.

Continue readingMolly of the Mall by Heidi L.M. Jacobs

Jane Austen-inspired novels are so numerous and varied that they form not just a distinct genre, but many subgenres. There are alternate points of view, prequels and sequels, genre crossovers, and modern retellings. Then there are novels that don’t adapt or retell or modernize, they simply appreciate. Molly of the Mall by Heidi L.M. Jacobs is one of these, and because it doesn’t hold too tightly to the source material, it is much more than another Austenesque novel.

Molly is a satire, a campus novel, a bildungsroman, and a romance. It’s an appreciation of Austen, but also of Woolf, Eliot, the Brontës, Hardy, Burns, and Daniel Defoe, among many others (Molly is named after Defoe’s scandalous heroine Moll Flanders, one of many delightful literary character names.) It’s also a celebration of Edmonton as a literary city.

Molly MacGregor is an aspiring “authoress”, studying English at the University of Alberta and selling shoes at West Edmonton Mall circa 1995. This is the era of card catalogues in the library and captive peacocks in the Mall – a far cry from today’s Edmonton, and far from where Molly wants to be. She finds Edmonton too cold, too bleak, and too bland a place from which to realize her literary and romantic ambitions. She spends much of her time in imagined conversation with her favourite authors and heroines, primarily “Miss Austen.”

Austen heroines don’t always have the most useful romantic advice, though. Upon spying her crush, Molly wondered:

“What would Persuasion’s Anne Elliot do now”? but then realized she would nod cordially, and proceed walking down the Mall, using her sensible millinery to prevent meaningful eye contact with a man not formally introduced to her. This might be why I so rarely summon Persuasion in my daily life decisions.

Austen’s oft-quoted writing advice, that “three or four families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on,” isn’t much help either. Molly laments that “coming from Edmonton was strike one for an aspiring writer.”

But Edmonton books are just as varied and diverse as Austen-inspired books, and as relevant to Molly’s interests, covering campus life (Michael Hingston’s The Dilettantes), retail ennui (Shawna Lemay’s Rumi and the Red Handbag), and West Edmonton Mall itself (the title story of Dina Del Bucchia’s Don’t Tell Me What To Do). There are even Janites in Edmonton: Melanie Kerr wrote Pride and Prejudice prequel Follies Past, and Krista D. Ball puts Lizzie and Darcy modern-day McCauley in First (Wrong) Impressions.

None of these books had been published in 1995, though. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf, another of her literary confidants, Molly would have to write the great Edmonton novel herself.

Molly aspires to serious literature, with plans for a “watershed Canadian coming-of-age novel,” and a “historically accurate, gothic bodice-ripper set in Saskatchewan”, but this novel is a comedy. Molly’s modern-day woes and Regency-era sensibilities make for delightfully funny observations about subjects as diverse as academia, consumerism, and the dateability of Oasis’ Gallagher brothers. The Edmonton-specific details are a treat, and mall workers the world over will relate to the staff rivalries, tedious closing shifts, and ubiquitous Boney M. Christmas music.

The humour rarely misses, though Molly’s novelistic plans, complete with comparisons between classic literary tropes and their Canadian equivalents (Heroines and Heifers, Passions and Pastures) are really only funny the first couple of times. Much better are Molly’s flights of fancy about classic literature, such as this Middlemarch-inspired daydream:

Passing Mall Security, I imagined bursting, breathlessly, into their inner sanctum, declaring, “This is urgent! I must address the shoppers! No time to explain.” I imagine they’d scratch their matching shaved heads and then hand over the PA system mic. “Attention shoppers,” I would start, “I have been reading George Eliot’s Middlemarch non-stop for the past three weeks, and I must tell you this. After 593 pages, Will Ladislaw has just kissed Dorothea. What does this have to do with you? It has everything to do with you. This is literature’s finest kiss. Here, let me read it to you.”

All this satire is hung on a rather low-stakes romantic plot. Molly has many suitors, but they’re nearly interchangeable, except for the “turtleneck” (Molly’s term for her pretentious classmates) who makes unwanted advances and is never heard from again. One of her admirers is her own sister’s ex-boyfriend, but this is never addressed. This seems like a situation rife for conflict in a book that could have used more of it.

The romance eventually comes to a neat conclusion, allowing the literary to take centre stage. Jacobs takes a real gamble in the last act, having Molly complete a year-end assignment on a “cheese poet” that is almost too outlandish, and too specifically Canadian, but she pulls it off. The details are best discovered by the reader, but it not only works as a comedic triumph, it also proves that Molly can indeed write from and about Edmonton, and that she doesn’t have to fall in with tired “nature and survival” CanLit tropes. A great Canadian novel can be about anything, even a shoe store in Phase III of West Edmonton Mall. It can even be funny.

You can read an Alice Munro story anytime you want

This post is just to say that you can read an Alice Munro story anytime you want. Even right now! A few possibilities:

- The New Yorker: Do you have free articles left at The New Yorker? Use one. Do you have a subscription? Even better, binge away – there are 61 stories dating back to 1977. Are you at your limit for free articles? I’m sure you know ways around that. For instance, I found out that you can borrow issues in Libby. If you don’t know where to start, here’s a guide to some of her stories available online.

- The library: Your library system probably has many Munro books, available right now, for free. Sixty-five in Edmonton, some with immediate ebook and audio access. There are, in addition to the major collections: book club kits, translations (in Chinese, Korean, Polish, French, and Spanish), early works, biographies, books for which Munro wrote a foreword, and books for which she acted as editor.

- The bookstore: Dozens of Munro books are in stock at my local chain bookstore, and while she’s not on hand at Glass, I know they’d order her in. If you order a newer edition, be aware that Penguin Canada has, for some reason, updated the cover art on a few of her books recently. I think they look kind of gross.

- Other: You could, of course, start a paid ebook or audiobook at any time. And you’d be hard pressed to find a used bookstore in Canada without a few of her books kicking around. Even outside Canada, I’ll bet you have pretty good access to a recent-ish Nobel winner.

That was a long preamble just to say that you could read a Munro story at any time. I’ve been thinking about this since reading her 2001 collection Hateship, Friendship, Loveship, Courtship, Marriage. I was feeling sappy about such a profound and entertaining reading experience, partly because I could have read it anytime in the past twenty years, but I put off till now. So I just want you to know, you don’t have to wait.

I don’t say this in a “life is short, read good books” kind of a way (though you probably should). Or in a “read her stories to develop empathy” kind of way (though if anyone’s writing can help with this, it’s hers). And definitely not in a “put your phone down and read for *self care*” kind of way (though again… perhaps…)

But more in a, “isn’t it amazing that you can?” kind of way. In a moment, on a whim, for free, you can be reading a story by arguably the world’s greatest living writer.

The closest approximation of the feeling I’m trying to convey is probably this iconic meme from Da Sharezone. I’m not saying you have to, but I think it’s important to know that you can. You can leave! Or you can read Munro.

Let’s also have a moment of appreciation for an author who did, indeed, “hit da bricks” (she hasn’t published much, if anything, since her Nobel win in 2013) rather than limp on, gathering up awards and distributing hot takes. I don’t know what Munro would post on Twitter, and given the proclivities of some of her contemporaries, I don’t want to know.

Three ways to get into poetry

I’m a fairly well read person. No, this post isn’t about what it means to be well read. Just take my word for it. I’ve read across many formats and genres, and many traditions and eras. I do have a weak spot though: poetry.

I remember learning exactly two poems in school. One was A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning by John Donne and the other was To His Coy Mistress by Andrew Marvell, and both are about dead white dudes who were feeling horny. Jeez, is it any wonder I wasn’t taken with it?

I’ve read three poetry collections so far this year, and I loved each of them. I’m not good at saying why, exactly, but I can tell you how I found my way in. Continue reading

CanLit for Cynics: Q&A with Peter Unwin

When I wrote about CanLit cynicism for carte blanche, I started with Alex Good’s book of essays, Revolutions (full Q&A here). Then, a very strange novel fell into my hands (actually, it was placed there by Kelsey at Freehand Books) and I knew these books were meant to be together. Searching for Petronius Totem is a strange, hilarious book, and author Peter Unwin is a bit strange and hilarious himself. Read on for the full Q&A.

When I wrote about CanLit cynicism for carte blanche, I started with Alex Good’s book of essays, Revolutions (full Q&A here). Then, a very strange novel fell into my hands (actually, it was placed there by Kelsey at Freehand Books) and I knew these books were meant to be together. Searching for Petronius Totem is a strange, hilarious book, and author Peter Unwin is a bit strange and hilarious himself. Read on for the full Q&A.

Many thanks to Mr. Unwin, and Ms. Attard at Freehand books!

2016 Year in Review #1: The Stats

You may notice something different about this year’s stats, compared to other years. Let’s see how long it takes to spot it…

I smelled 0% of the paper books because that’s weird.

Books Read

- Books read in 2016: 35, down from 69 in 2015. That was on purpose, though. And I’m not counting rereads, kids books, or books I read for work.

- Shortest book: Bluets by Maggie Nelson (112 pages)

- Longest book: Cecilia by Frances Burney (1,056 pages)

- Format: 97% paper, 3% ebook, 0% audio (compared to a third of my reading on ebook and audio last year)

About the Author

- 100% female (58% in 2015)

- 34% person of colour (up from 20% 2015)

- 37% Canadian (same as 2015) 38% American, 11% British, and 1 each: Korean, Japanese, French, Filipino.

- Three Edmonton-area authors this year, being generous with one who moved recently!

… did you catch it? Yes, I did the #readwomen thing this year, and my experience will be covered in a separate blog post. Brace yourselves: unlike many who do this sort of thing, I did not come to any shattering realizations, and I *cannot wait* to read some dudes in 2017.

The book that started it all.

Genres and Lists

- 11% classics (same as 2015), 63% contemporary lit fic (about the same as previous years), 11% nonfiction (all memoirs), and a handful of erotica, poetry, and graphic novels.

- 2 1001 Books for a total of 127 read.

Probably gonna mix it up a bit next year, say, read some nonfiction that isn’t memoir?

Ratings

- 17% were rated five stars (up from 11% last year), 49% were four stars, 23% were three stars, 14% were two stars and poor Nora Roberts gets just one.

- The most underrated book was After Claude, which I rated a 5, compared to average 3.55 rating on Goodreads. Which I assume is due to people getting offended, which is the whole point.

- The most overrated book was The Liar, which I rated a 1, compared to average 3.94 rating. It was just bad.

Lemme in, Something Awful! I won’t stay long, I promise!

Blog Stats

- Headed for about 17,000 page views in 2015, down from 23,000 in 2015. And 11,000 visitors, down from 15,000.

- I’m not panicking, because my review of The Fault in Our Stars, which amassed 7,000 views in 2013-2015, was viewed just 400 times this year. Looks like kids writing papers have moved on to another book. Similarly, my review of Sleeping Beauty is not pulling the numbers it used to (nor am I seeing as much filth in my search terms). I think a lot of my traffic in 2014/2015 was artificial due to people landing on those posts – and quickly clicking away. They were never my readers anyway. The moral is: never review YA or erotica.

- An Oryx and Crake readalong recap from 2013 continues to perform, due to a post on a Something Awful forum which I’m sorely tempted to pay for so I can see what it is… anyone a member? Hit me up!

- On course for 45 posts this year, up from 39 posts in 2015.

- Most viewed post of 2016 is that mysterious Oryx and Crake one.

- Most viewed post that was actually written in 2016: Intro post of the Cecilia readalong, likely due to a little help from CBC.

- Least successful post in 2016: Short Story Advent Calendar Video Reviews. Same as in 2015, it’s a Booktube post. Okay, I get it, you guys don’t like the Booktube…