Get your TBR pile down to zero with this one weird trick

The trick is to have your house burn down. Instant TBR zero.

Of course you also lose all your other TB piles: To Be Worn, To Be Eaten, To Be Slept on, To Be Cooked with, To Be Remembered By…

My house caught on fire on December 18. It started in the kitchen (cause still being determined) and was contained and put out quickly. I’d only been out of the house for about 45 minutes when I started getting calls from neighbours. It’s a mindfuck, because my house didn’t actually burn down, and my books, along with most of our belongings, weren’t actually reduced to ash. The smoke, soot, water, and asbestos are what get you. Despite the house looking okay from the outside, we lost almost everything we owned.

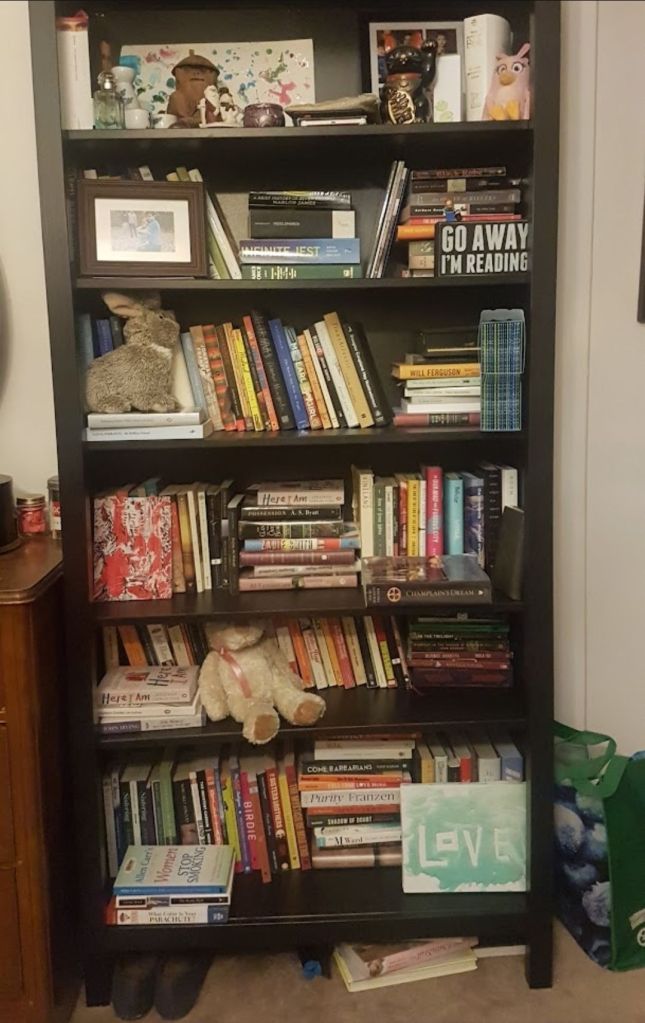

I didn’t have a single book “pile” or shelf. I had books on, under and on top of shelves, as well as on desks, coffee tables, bedside tables, and in drawers and closets. I also, thankfully, had a Google Sheet with a complete and up-to-date listing of each one of those books, including origin and cost for the more recent ones. (Did I have an inventory of any other items in the house? Of course not. BUT YOU SHOULD. START ONE NOW. TRUST ME.)

I don’t even have a “TBR” tab in my spreadsheet. It’s not something I think about much. I have a “wishlist” of books I don’t own but might want to, based on reviews or recommendations – the most recent addition is Bouvard and Pécuchet by Flaubert, as recommended in the NYT’s “Read like the Wind” newsletter. I also have tabs related to various “projects,” like reading the works of Dostoyevsky, or the 1,001 Books list. These are all TBRs of sorts.

But what people usually mean by TBR is “books you own but haven’t read.” TBRs sometimes include unread ebooks, but usually don’t include books you have on hold at the library, or books you are thinking about buying. A TBR pile is a real thing that you spent money on. By filtering on “unread” and filtering out “Kindle” and “Kobo”, I see that I had a TBR pile of 108 books, as of the morning of December 18, anyway.

In online bookish circles, TBRs are often framed as a problem, or at least something to be managed, an indicator of consumerism at best and hoarding at worst. TBR challenges abound; people have plans to get to a zero TBR, or under 30, or under 100. They will do this in a year, or six months, or as long as it takes.

I confess, “TBR” content is among my least favourite bookish content (if you are someone who does TBR stuff online, I don’t mean you. I especially don’t mean Cathy!). There’s not much to say about a book you haven’t read, after all, and I find the accounting side of TBRs (books in, books out, monthly reckonings etc.) pretty tedious, unless it’s my own.

I read some TBR posts and watched some TBR videos for the purpose of writing this, and found that most of the “tips and tricks” for TBR challenges have to do with “reading more”, not “buying less”, and often it’s not even about finding more time to read, or speeding up your rate of reading (though that content is certainly out there too). It’s more about convincing yourself to read from your pile, through random chance (spins, jars) or incentives (no buying books until the TBR is under 100.)

TBR challenges don’t often get beyond the here and now, and into the existential question of how many books you will read before you die, or more to the point, how many books you will not read. I started reading from the 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die list before I even started blogging, i.e. before I’d heard of a TBR, and it’s the kind of list you don’t ever really expect to finish, so I guess I’ve always taken the long view on this. A pile of 108 books is less daunting if you think of what you might read over the next 40 or 50 years. And I don’t think it’s something to beat yourself up for.

Let your TBR or other book lists be about anticipation instead. Anticipate the great books you’re going to read, and the ones so bad they’re good. Anticipate filling in the blanks on things you’re interested in, and going off on tangents into new topics. Anticipate reading an author’s complete works and then adding their biographies, letters, and criticism to your ever-growing and changing TBR. Document it, be honest about it, but let it be a positive thing.

My TBR pile is gone. But I still have plenty of books that are “to be read” – almost every book ever written, technically. And of course, two months on from the fire, my TBR has regenerated a bit. Here it is, in its entirety:

- The Tenderness of Wolves by Stef Penney (from a Little Free Library and solely because the blurb, “Like Cold Mountain but colder”, made me laugh out loud)

- My Heavenly Favourite by Lucas Rijneveld (my first post-fire purchase)

I have two more, non-TBR books in the house: A smoke-damaged, signed first edition of Freedom by Jonathan Franzen (recovered along with other sentimental items – I did NOT run back into the house for it) and The Birthday Party by Laurent Mauvignier, which had been sitting on my desk at work. We will rebuild – in 2025, or whenever I get back into my house!

Here’s my actual “one weird trick” for dealing with your TBR: Don’t worry about getting to zero, because you might get hit by a bus tomorrow – or your whole pile might go up in flames.