Category: Reviews

Novellas in November Update #3: The Suicide Shop, The Testament of Mary and The Wizard of Oz

November is over so in the interest of time, these are going to really short reviews of really short books! Lost? Check out my previous posts:

- Novellas in November: Introduction

- Novellas in November Update #1: Summer, The Pearl, The Night Before Christmas, and Bonjour Tristesse

- Novellas in November Update #2: Memories of my Melancholy Whores and a Vlog

The Suicide Shop by Jean Teule

My rating: 4/5 stars

Goodreads

Synopsis:

With the twenty-first century just a distant memory and the world in environmental chaos, many people have lost the will to live. And business is brisk at The Suicide Shop. Run by the Tuvache family for generations, the shop offers an amazing variety of ways to end it all, with something to fit every budget. The Tuvaches go mournfully about their business, taking pride in the morbid service they provide. Until the youngest member of the family threatens to destroy their contented misery by confronting them with something they’ve never encountered before: a love of life.

This book is like The Addams Family: morbid, cheesy, campy, and ultimately harmless. I was reminded of my years working in a haunted house – the one located under the roller coaster in West Edmonton Mall, which is supposedly haunted by the people who died in the derailing in 1986. We had a Addams Family “electrocution test” machine which supposedly tests your ability to withstand electric shocks conducted through two metal rods that you hold onto, but the rods actually just vibrated. But I digress. This book was weirdly great. It was all those things the Addams Family are – cheesy and campy in the extreme – but somehow it worked. It’s a futuristic fairy tale with a strong moral message at the end, and usually I hate that, but I don’t know, I guess my 90s nostaligia got the better of me. What can I say, I really loved laughing at dumb tourists who paid $2 to hold on to what were essentially a couple of vibrators.

The Testament of Mary by Colm Toibin

My rating: 5/5 stars

Goodreads

Provocative, haunting, and indelible, Colm Tóibín’s portrait of Mary presents her as a solitary older woman still seeking to understand the events that become the narrative of the New Testament and the foundation of Christianity.

I’m not going to do this book justice in a short review like this, so I will direct you to Another Book Blog and urge you to read it and I will quote this passage, which says absolutely everything:

‘I was there,’ I said. ‘I fled before it was over but if you want witnesses then I am one and I can tell you now, when you say that he redeemed the world, I will say that it was not worth it. It was not worth it.’

Okay, I will also say that this book reminded me of Emma Donaghue’s Room, which might seem odd, but they’re both stories of mother and son (or Mother and Son in this case,) maternal guilt, and the inability of parents to protect their children from the world. Even if he’s locked in a room. Even if he’s the son of god.

The Wizard of Oz by Frank L. Baum

I’m not done this one yet, but must note that I’ve been reading it to my (almost) four year old, and it’s been a delight. As readers, we get so excited about reading to our children, but we don’t realize that the first few years are torture – most baby and toddler books are awful. If it’s not super-schmaltzy Love You Forever, it’s some Disney marketing material barely disguised as a book. This is my first experience reading a real chapter book with my kids, and I get it now. Reading to your kids IS awesome. Especially when you get to read about messed up stuff like killer flying monkeys and opium-induced stupors.

Bonus: Some Novella Publishers of Note

So, you probably enjoyed this event SO MUCH that you want to read a bunch of novellas, right? Here’s a few publishers that specialize in novellas to get you started:

- Melville House: The Art of the Novella Melville House Books publishes a collection of novellas by the likes of Austen, Eliot, Proust, Dostoyevsky, and Mr. Melville himself. You can buy the whole collection of 52 novellas for a pretty decent price ($410 US) or you can subscribe and receive a novella every month. You can give this as a gift, too – like the Jelly of the Month Club, it’s the gift that keeps on giving. (Hint, hint to a certain sister of mine who is my secret Santa this year.)

- New Directions: Pearls Confession: I hate these covers. But it’s a great collection of classic novellas, reissued, and includes works by Fitzgerald, Gogol, and Borges. I am giving this collection the side-eye for not including any female authors, though.

- Black Hill Press: The only publisher on this list that deal exclusively in novellas, and American novellas in particular, this indie press doesn’t boast any big names, but wouldn’t it be cool to discover a new author through a novella? I’m expecting a review copy of Another Name for Autumn any day now.

Thank you Another Book Blog for hosting! Go check out his epic vlog wrap up – literally epic, it’s 45 minutes long!

Hellgoing by Lynn Coady

My rating: 4/5 stars

Goodreads

Synopsis:

With astonishing range and depth, Scotiabank Giller Prize winner Lynn Coady gives us nine unforgettable new stories, each one of them grabbing our attention from the first line and resonating long after the last.

Equally adept at capturing the foibles and obsessions of men and of women, compassionate in her humour yet never missing an opportunity to make her characters squirm, fascinated as much by faithlessness as by faith, Lynn Coady is quite possibly the writer who best captures what it is to be human at this particular moment in our history

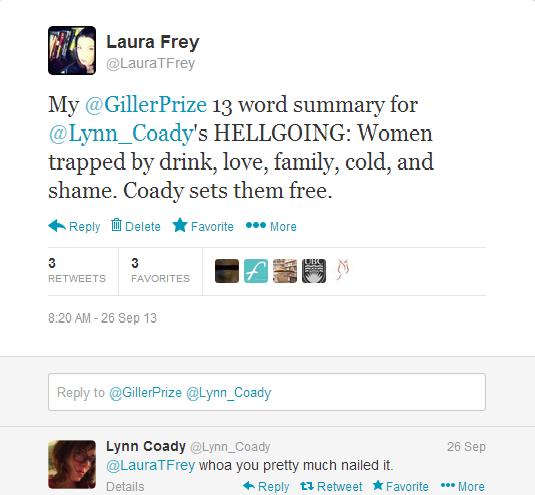

I apologize for posting the following self-congratulatory tweet, but for book bloggers, I don’t think it gets better than being acknowledged by an author you love. The Giller Prize’s Twitter account asked us to review a long-listed book in 13 words exactly:

It’s true, though, “trapped” was the first word that came to mind after reading this collection. Reading these stories was uncomfortable and claustrophobic. I was literally squirming at times. Coady gets us so close to her characters, it’s almost embarrassing, and I have a real problem with vicarious embarrassment. I’m one of those people who have to change the channel when a character is too exposed, or being made a fool of.

The first and last stories were the strongest. Maybe that’s just primacy bias, or maybe it’s my own experience that made these stories devastating – the first is about an alcoholic, the second about a teenage pregnancy, both topics that tend to punch me in the gut.

“Wireless” opens with a hangover, and it’s one of the best descriptions of one I’ve read:

She lay flat on her back for twenty minutes, gauging the pain, the depth of her dehydration. The song in her ears. She sat up, and a second later her pickled brain slid back into its cradle in the centre of her cranium. Time to throw up.

I haven’t had a hangover in five years and reading that made me shudder. The whole story is disconnected and fuzzy, like that poor, pickled brain. What’s with the two mentions of Beanie Babies? What’s with the title? What’s the deal with Ned, the man Jane meets, another alcoholic who is lying to her for unknown reasons? We never find out.

The last story is “Mr. Hope,” and it’s another strange one. This is the one that really prompted my “uncomfortable” response. There’s something off about the whole thing and I can’t figure out what. Is it because the narrator refer’s to her teachers large belly as his “D,” as in the shape of a “D,” given the (gross) internet meme thing “she wants the D?” Because the way Mr. Hope interacts with the kids is kind of age inappropriate, and you wonder what else inappropriate is going on? Like this scene, where he is inexplicably trying to force a grade one class to come up with a definition for “love:”

“You: gap-tooth.”

“Love is when you hold a puppy.”

Mr. Hope slammed his fist against our sweet-faced grandma-teacher’s desk.

“LOVE IS NOT,” he bellowed, “WHEN YOU HOLD A PUPPY.”

Behind me, I could hear someone’s breath hitching rapidly in and out and I tried to shush whoever it was as quietly as I could.

“Where is it?” Mr. Hope demanded to know. “What is it? Think about that, people. You’re all so sure about this thing, and you can’t even answer the question. I’m not asking you when it is. A rock is a small hard round thing. Okay, that’s not great, but at least it’s a start. So what kind of thing is love? Big or little? Soft or hard? Black or white? Or coloured?”

And it gets more awkward from there. I reread this story in it’s entirety for this review, and it struck me differently this time. That’s the great thing about these stories – they’re ambiguous, not in an unresolved way, but in a way that you can read into differently each time.

A few of the other notable bits include:

- A story that’s made the best use of texting I’ve encountered in fiction- and I know that’s quite a feat, have heard from authors who’ve set their stories in the past specifically to avoid having to deal with technology,

- An Edmonton winter story that should have been in the 40 Below anthology; I know so because I drove myself nuts searching for it in my copy of 40 Below while writing my review,

- Stories about self-harm, anorexia, self-doubt, and general dysfunction. Cheery stuff.

Some of these stories stuck with me. Some of them made little impression at all. I want to see what Coady can do with a novel-length story. I know, it’s probably a book-snobbish way to think, but it’s true. Rather than the recent and critically acclaimed The Antagonist, I want to start with Strange Heaven which sounds right up my alley. Another story about a teenage mom – I really should branch out.

The Giller Effect

Reviewing the book’s Goodreads page, I was surprised to see only 101 ratings. The Giller Prize was announced a few weeks ago, and the long and short lists have been out for months. I’m not sure if Goodreads ratings is a valid criteria, but it’s easy to do a few comparisons:

Past Five Giller Winners:

- Hellgoing – 101 ratings

- 419 – 4000 ratings

- Half-Blood Blues – 6563 ratings

- The Sentimentalists – 1691 ratings

- The Bishop’s Man – 3187 ratings

The other 2013 shortlisted titles have around 100 ratings each too, so maybe they just need more time. Though somehow long-lister Claire Messud has nearly 10,000 ratings for The Woman Upstairs!

To ensure this wasn’t a Canada thing, I checked out the recent National Book Award recipient Good Lord Bird – 500ish ratings. Maybe people (or, more specifically, people who are active on Goodreads) don’t give a shit about award winners. Compare (and weep) with Dragon Bound’s 15,000 ratings.

As for whether or not Hellgoing deserved to win, well, you’ll have to wait for my review of Caught for my final thoughts. I only read these two, so I can’t weigh in on the travesty of The Orenda not making the shortlist. Totally a coincidence that I read the two female authors on the shortlist too, I swear!

The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins

My rating: 3/5 stars

Goodreads

Read-along post #1

For someone who does a lot of read-alongs, sometimes I feel like I’m not very good at them. On the appointed day for our midway posts, I decided to post nothing and finish the book instead. I also feel like a bit of an outsider, as everyone else is positively swooning over The Moonstone, while I was left a little cold.

For a detective/mystery story, I didn’t feel much suspense at all for 90% of the book. It was only at the very end, when reading the factual, precise account of what happened to the moonstone, that I felt any real urgency to keep reading. Oh, I was curious about what happened to the moonstone. Sure. Who wouldn’t be? But the book utterly failed to make it matter beyond the whodunit aspect and that just wasn’t enough for me.

I think the ambivalence was intended, because the heroine and owner of the jewel is just awful, not to mention it comes to be in her family’s possession through murder. And colonialism. Her uncle is basically looting in India and kills a few Indians in the process. I don’t know what the general feelings on colonialism were in 1850, but the set up is so egregious I can’t help but think Wilkie (yes, we’re on a first name basis) wanted us to root for the Indians. India was still nearly 100 years from independence (wow) but really, it’s their damn diamond, maybe, I don’t know, give it back rather than be cursed and ruin everyone’s lives. JUST A THOUGHT.

What I don’t think was intended was the failure (to me) of the romance between Rachel and her first cousin Franklin. I struggle with the cousin thing. I know, different time, different culture and so forth. Maybe it’s because I share a family resemblance with a lot of my cousins so I just imagine these two making out and looking the same and it’s very Flowers in the Attic. Maybe it’s because Rachel has two romantic interests and they’re BOTH first cousins and I just think she needs to get out more. But I really didn’t care if Rachel and Franklin ended up together or not.

All that said, I did enjoy the book and would recommend it on the strength of the narrative structure alone. I’m a sucker for an epistolary novel, and Wilkie does it so well. We begin the novel with sweet, self-deprecating, sexist Betteredge, the Verinder family butler, hopelessly devoted to his Lady, his pipe, and Robinson Crusoe. You’d be hard pressed to find a more endearing narrator (in spite of the rampant sexism) or a funnier one. Pretty sure I snorted when I read this:

On hearing those dreadful words, my daughter Penelope said she didn’t know what prevented her heart from flying straight out of her. I thoughts privately that it might have been her stays.

Betteredge repeatedly addresses himself directly to the reader, here admonishing us to pay attention. Guilty as charged, I was totally thinking about my new bonnet while I was reading this…

Clear your mind of the children, or the dinner, or the new bonnet, or what not. Try if you can’t forget politics, horses, prices in the City, and grievances at the club… Lord! haven’t I seen you with the greatest authors in your hands, and don’t I know how ready your attention is to wander when it’s a book that asks for it, instead of a person?

The next narrator is one Miss Drusilla Clack and she was my favourite part of the whole book. I wish she’d narrated the whole thing. I wish the book was about her. She’s so delightfully hypocritical and a loves to play the martyr. She has a way with words; remarking on France’s “popery” and her aunt’s “autumnal exuberance of figure.” And then there are her tracts. Modern readers might be familiar with Chick Tracts (I was personally handed one at a Marilyn Manson concert in 1997 which is definitely in the top ten of “most 90s things that ever happened to me”) but Miss Clack’s tracts sound much more entertaining:

Here was a golden opportunity! I seized it on the spot. In other words, I instantly opened my bag, and took out the top publication. It proved to be an early edition of the famous anonymous work entitled THE SERPENT AT HOME. The design of the book is to show how the Evil One lies in wait for us in all the most apparently innocent actions of our daily lives. The chapters best adapted to female perusal are “Satan in the Hair Brush;” “Satan behind the Looking Glass;” “Satan under the Tea Table;” “Satan out of the Window” — and many others.

Seems like Clack needs to reread a few of those tracts herself. #Humblebrag alert:

On rising the next morning, how young I felt! I might add, how young I looked, if I were capable of dwelling on the concerns of my own perishable body. But I am not capable– and I add nothing.

I made a ton of annotations in Betteredge’s and Clack’s sections, and nearly none in the ensuing ones, narrated by the family’s lawyer, that dreamy first cousin Franklin, and a Mr. Jennings who I can’t really explain without spoilers. The rest of the book was interesting and well written and the ending was satisfying, but I just missed the first two narrators so much, I couldn’t get into it.

The Read-Along

Despite not loving the book, I had a lot of fun with this read-along! The #readWilkie hashtag was active, the bloggers were committed, and there is something very endearing about a group of girls so earnestly in love with a 19th century author (no judgement, I’m currently crushing on Anton Chekhov.) I heartily encourage you to visit the other #readWilkie bloggers, who may do a better job of convincing you to read The Moonstone.

- Our host Ellie at Lit Nerd

- Riv at Bookish Realm

- Juliana at Epilogues

- Hanna at Booking in Heels

- Kayleigh at Nylon Admiral

- Charlotte at Lit Addicted Brit

- Melbourne on my Mind

- Ellie at Book Addicted Blonde

There are a few more, but these are the bloggers who posted a mid-way post.. you know… who followed the rules.

THANK YOU to Ellie for hosting, and I eagerly await the flood of reviews at the end of the month!

Novellas in November Update #1: Summer, The Pearl, The Night Before Christmas, and Bonjour Tristesse

Mini reviews for mini novels! See the start up post on Another Book Blog, and my introductory post here.

My rating: 5/5 stars

Goodreads

Synopsis:

A new Englander of humble origins, Charity Royall is swept into a torrid love affair with an artistically inclined young man from New York City, but her dreams of a future with him are thwarted.

I started reading Summer at the end of October so I could squeeze one last regular classic in before Novellas in November kicked off. I knew nothing about it except it was free on my Kobo. I quickly found out it was a novella. Score! Oh and it’s supposedly an erotic novella. Double score. And yeah, it was pretty hot! I mean, check out this filth:

All this bubbling of sap and slipping of sheaths and bursting of calyxes was carried to her on mingled currents of fragrance.

Bubbling sap indeed. And this:

A clumsy band and button fastened her unbleached night-gown about the throat. She undid it, freed her thin shoulders, and saw herself a bride in low-necked satin, walking down an aisle with Lucius Harney. He would kiss her as they left the church….She put down the candle and covered her face with her hands as if to imprison the kiss.

This book is part Tess of the D’Ubervilles, part VC Andrews’ Heaven and all kinds of awesome. Tess because of the pastoral and natural elements, and the fallen woman thing, and Heaven because our heroine comes from dirt poor, likely inbred mountain folk and you know what they say, you can take the girl off the mountain…

Charity is such an interesting heroine because she’s selfish, flighty, and well, not that bright. Or at least not at all interested in intellectual pursuits. A realistic teenager, in other words. I’m always surprised by a non-bookish hero, and think that it must be difficult for a writer to get into that head space. Wharton nails it. This book was a delight and my I think it just knocked House of Mirth out of my “favourite Wharton” spot.

Here’s a lovely, more detailed review, if I haven’t convinced you to pick this up. Continue reading

40 Below: Edmonton’s Winter Anthology edited by Jason Lee Norman

40 Below: Edmonton’s Winter Anthology edited by Jason Lee Norman | Published in 2013 by Wufniks Press | Paperback: 205 pages | Source: Review copy from the editor

My rating: 4/5 stars

Goodreads

Synopsis:

40 Below is Edmonton’s Winter Anthology. Stories, poems, and essays about or inspired by winter in Edmonton.

Like many (most?) book bloggers, I have some writerly ambitions of my own. Last winter, I spent the tail end of my maternity leave picking away at a submission for the 40 Below anthology. There’s nothing like a new baby and a two-year-old to make you feel the isolation of an Edmonton winter, so my story wasn’t particularly positive. Nor was it particularly good. Earier this year I received a very nice, personalized rejection email from editor Jason Lee Norman (author of Americas, my review here.) I have absolutely no hard feelings (it was pretty bad) and really enjoyed the whole process of writing and revising. If nothing else, it gave me something to do at 2am other than the usual dead-eyed scrolling through Twitter.

I was excited to find out who did make the cut. It’s a who’s who of Edmonton writers, including a whole bunch who’ve been reviewed here on Reading in Bed: Michael Hingston, Jessica Kluthe, Diana Davisdon, and Jennifer Quist. Not that it’s all #yegwrites establishment. There are plenty of authors I’ve never heard of, and even a couple of kids. Variety is the strong point of the collection. With that in mind, here are a few of my picks:

- Story that I related to on a personal level: Sirens by Diana Davidson. It actually resulted in a Twitter therapy session as two other Edmonton book bloggers and I read it around the same time. They both happen to be pregnant, and Davidson’s story is about a first-time mother struggling with postpartum depression in the dead of winter. I brought my first baby home in literal 40 Below weather and went through postpartum depression too. Davidson gets it just right and I was shaking at the end.

- Favourite very short story, I’m talking 9 sentences: Moon Calling by Don Perkins. Mostly for the last sentence: “But that moment of the infant embracing its own future ripeness, that’s the moon that calls.” You have to read the other eight, trust me.

- Story that’s really a parenting lesson: A Winter Lesson by Alan Schietzsch. That lesson? Go outside. Your kids don’t feel the cold.

- Story that reminds you exactly of being a kid: Sandwich Season by Margaret MacPherson. Kids are weird and do weird things, just like in this story.

- Story that I didn’t want to end: Conversation by Ky Perraun. I read it and then read it again because I need to know what happened!

This book is an obvious buy for anyone who is into the arts scene here in Edmonton, but I think it has some crossover appeal too. It’s actually a great gateway drug for people who don’t read short stories. The pieces tend to be very short, and the theme is very accessible, so it’s easy to dip in and out. It would be so cool if people in other Northern climates, or even those who don’t talk about wind chill for six month of the year, picked up this book. I’d love to read some non-local reactions. I also think it would make a great bathroom book and I mean that as a compliment. I am very picky about what books are kept in my bathroom.

Oh and if you were wondering, my story was about my memories of New Years Eve 1997, when we got the first snow of the year and the temperature dropped from zero to minus twenty over the course of a few hours. I was out without a coat (because: teenager) and made a rash decision based on getting out of the cold that affected my life for years afterward. Maybe I’ll try to fix it up someday!

I hear winter’s about to hit Edmonton this weekend. Should be plenty of snow on the ground for the two 40 Below launch events:

- 40 Below Launch at Block 1912: Sunday Nov. 17, 2:00 pm. This is the one I’m going to, so obviously it’s the place to be.

- 40 Below Launch at Audreys Books: Tuesday Nov. 19th at 7:00pm. Who knows, maybe I’ll show up here too.

Thank you to the editor for sending me a review copy of this book!

Stoner by John Williams

Stoner by John Williams | Published in 2006 by NYRB Classics (originally published in 1965) | Paperback: 278 pages | Source: Library

My rating: 5/5 stars

Goodreads

Synopsis:

William Stoner is born at the end of the nineteenth century into a dirt-poor Missouri farming family. Sent to the state university to study agronomy, he instead falls in love with English literature and embraces a scholar’s life, so different from the hardscrabble existence he has known.

And yet as the years pass, Stoner encounters a succession of disappointments: marriage into a “proper” family estranges him from his parents; his career is stymied; his wife and daughter turn coldly away from him; a transforming experience of new love ends under threat of scandal. Driven ever deeper within himself, Stoner rediscovers the stoic silence of his forebears and confronts an essential solitude.

John Williams’s luminous and deeply moving novel is a work of quiet perfection. William Stoner emerges from it not only as an archetypal American, but as an unlikely existential hero, standing, like a figure in a painting by Edward Hopper, in stark relief against an unforgiving world.

Stoner must be the most famous “under appreciated” book around. It seems that everywhere I look, a blogger or a literary critic is entreating us to give this forgotten classic a chance. It was reprinted by the highly regarded NYRB Classics in 2006, and just a few months ago was endorsed by Ian MacEwan. But, it’s not on any of those top 100 or 1001 lists, and its Wikipedia page is just a tragedy. And it did, predictably, make an appearance on BookRiot’s Most Underrated Books list.

Stoner was my Classics Club Spin pick, and it was from my “dreading it” list. I was intimidated, as the bloggers talking it up were all really smart and I was afraid I would be in over my head; and I was managing expectations, because the last time I got all excited because of a bookish-internet frenzy I was let down.

Oh, and I could tell from the blurb that this was going to be one of those “poor little privileged white dude is bored, cheats on his wife but feels really bad and conflicted about it, wah wah, epiphany of some sort, the end” stories. So there was that. And it absolutely is one of those stories. But, once I got over myself and started reading, I quickly realized that, like most people’s real lives, you can present William Stoner’s life as a happy story or a sad story, depending how you look at it:

- The “Quit Whining, Privileged White Dude” version: Stoner doesn’t have to fight in either world war. He loves literature, and is able to study it then teach it. He attains tenure, and so isn’t really at risk of losing his livelihood during the depression. He marries the first girl he ever asks out. They have a daughter without having to try too hard (more on THAT later.) He has a torrid mid-life love affair, but his marriage survives. He lives a quiet life and dies surrounded by his family.

- The “I Feel Really Bad Now” version: Stoner grows up in abject poverty. He alienates his parents when he goes to University, and alienates his friends when he chooses not to enlist in WWI. He discovers a love of literature but his career is mired in petty politics and he never achieves any real recognition. He marries a deeply damaged woman who seems wholly incapable of love. He enjoys a close relationship with his daughter until his wife cruelly turns her against him. He finally finds a woman he can love and is forced to give her up. His never reconciles with his wife, and his daughter descends into alcoholism. He dies a protracted, painful death, having never resolved any of these issues. Continue reading

Pilgrimage by Diana Davidson

Pilgrimage by Diana Davidson | Published in 2013 by Brindle & Glass | Paperback: 288 pages | Source: Review copy from the author

My rating: 3.5/5 stars

Goodreads

Synopsis:

Pilgrimage opens in the deep winter of 1891 on the Métis settlement of Lac St. Anne. Known as Manito Sakahigan in Cree, “Spirit Lake” has been renamed for the patron saint of childbirth. It is here that people journey in search of tradition, redemption, and miracles.

On this harsh and beautiful land, four interconnected people try to make a life in the colonial Northwest: Mahkesîs Cardinal, a young Métis girl pregnant by the Hudson Bay Company manager; Moira Murphy, an Irish Catholic house girl working for the Barretts; Georgina Barrett, the Anglo-Irish wife of the hbc manager who wishes for a child; and Gabriel Cardinal, Mahkesîs’ brother, who works on the Athabasca river and falls in love with Moira. Intertwined by family, desire, secrets, and violence, the characters live one tumultuous year on the Lac St. Anne settlement; a year that ends with a woman’s body abandoned in a well.

Set in a brilliant northern landscape, Pilgrimage is a moving debut novel about journeys, and women and men trying to survive the violent intimacy of a small place where two cultures intersect.

If you ever need a reminder of why access to reliable birth control is so important, read this book. Today, women go on the pill in adolescence and have IUDs inserted as soon as postpartum healing allows. We send our partners to be “snipped” or we go to the corner store and choose from an array of gimmicky condoms of dubious “for her pleasure” claims. One hundred years ago, women were at the mercy of their fertility or lack thereof. Or, more to the point, they were at the mercy of the men that might make them pregnant. Diana Davidson takes us back in time, but not far from home, to tell us about three women whose lives were changed by pregnancy. Continue reading

Love Letters of the Angels of Death by Jennifer Quist

Love Letters of the Angels of Death by Jennifer Quist | Published in 2013 by Linda Leith | Paperback: 202 pages | Source: Review copy from publisher

My rating: 4/5 stars

Synopsis:

A breathtaking literary debut, Love Letters of the Angels of Death begins as a young couple discover the remains of his mother in her mobile home. The rest of the family fall back, leaving them to reckon with the messy, unexpected death. By the time the burial is over, they understand this will always be their role: to liaise with death on behalf of people they love. They are living angels of death. All the major events in their lives – births, medical emergencies, a move to a northern boomtown, the theft of a veteran’s headstone – are viewed from this ambivalent angle. In this shadowy place, their lives unfold: fleeting moments, ordinary occasions, yet on the brink of otherworldliness. In spare, heart-stopping prose, the transient joys, fears, hopes and heartbreaks of love, marriage, and parenthood are revealed through the lens of the eternal, unfolding within the course of natural life. This is a novel for everyone who has ever been happily married — and for everyone who would like to be.

I thought this was going to be another one of those books that hits home, and it was, but not for the reasons I thought. I knew that the main character’s mother dies and that we learn about how his wife is able to support him by tuning into his needs. Quist says this of that opening scene (read the whole interview at her publisher’s web site):

The fact is, the opening scene is based on a real experience my husband and I shared when his father died unexpectedly and alone. During that disaster, I coped with my own shock and grief by making my husband’s feelings and perceptions the only things that mattered to me. It was a desperate strategy meant to get both of us through the experience as undamaged as possible. I went back into that hyper-empathetic frame of mind to write the first chapter of the novel. I’d been there before. The rest of the book – the fiction – evolved out of that truth.

I figured it was the story of a happy marriage made even happier by a traumatic event. That’s… not how it works for me. My husband lost his father four years ago, just three weeks before the birth of our first child, which was traumatic and accompanied by postpartum depression. We turned inward rather than toward each other. Neither of us were good spouses during that time. So, I was prepared for a literary smack upside the head – why didn’t this make us stronger? Why couldn’t I put my needs aside when my husband was grieving? Why couldn’t he see that I was struggling too?

But the book wasn’t about smack downs at all. Nor was it a marriage manual (though Quist gives some great pointers here.) It was, duh, a story, and once I got over the second-person perspective I was immersed and not worrying about the state of my marriage. Love Letters speaks directly to my tastes in many ways – the prairie and maritime settings, the morbidity, the Catholic relics, the heroine who is most definitely a feminist and shares my incapacitating fear of bugs (if I ever see a tar sand beetle I will die.) Continue reading

Rosina, The Midwife by Jessica Kluthe

Rosina, the Midwife by Jessica Kluthe | Published in 2013 by Brindle & Glass | Paperback: 216 pages | Source: LitFest

My rating: 4/5 stars

Goodreads

Synopsis:

Between 1870 and 1970, twenty-six million Italians left their homeland and travelled to places like Canada, Australia, and the United States, in search of work. Many of them never returned to Italy.

Rosina, the Midwife traces the author’s family history, from their roots in Calabria in the south of Italy to their new home in Canada. Against this historic background, comes the story of Rosina, a Calabrian matriarch and the author’s great-great-grandmother, the only member of the Russo family to remain in Italy after the mass migration of the 1950s. With no formal training, but plenty of experience, Rosina worked as a midwife in an area where there was only one doctor to serve three villages. She was given the tools needed to deliver and baptize babies by the doctor and the local priest, and, over the course of her long career, she helped bring hundreds of infants into the world.

Enhancing the stories and memories passed down through her family with meticulous research, Kluthe has, with great insight, created not only Rosina’s story, but also the entire Russo family’s. We see her great-grandfather Generoso labouring through the harsh Edmonton winter to save enough money to buy passage to Canada for his wife and children; we glimpse her grandmother Rose huddled in a third-class cabin, sick from the motion of the boat that will carry her to a new land; and we watch, teary-eyed, as her great-great-grandmother Rosina is forced to say goodbye, one by one, to the people she loves.

I recently wrote about books that hit home and I mentioned a couple of books that talk about teen pregnancy and miscarriage, but this is The One that inspired the post, and the one I couldn’t review until I talked about That.

That said, there’s more to this book than pregnancy. Actually, pregnancy and childbirth didn’t play as big a role as I thought they would. I was expecting something like The Birth House. Pregnancy, birth, and loss all play a part, but this is really a story about identity and home.

I was also expecting fiction. I didn’t know Rosina was a memoir until I was offered a copy by the staff at LitFest, a non-fiction festival. It reads very much like fiction. I kept forgetting, and thinking “I wonder why she chose this setting,” or, “I wonder what the purpose of this character is,” then realizing that the setting was really where it happened and the character was a real person. Those questions are still valid though. In non-fiction, the author still chooses what to describe in detail, and what to gloss over. She chooses who has a voice – in this case, herself, and her great great grandmother Rosina – and who stays in the background.

Kluthe chooses to give a voice to a woman who stayed behind when her family left for Canada, who lost her husband as a young woman with young children, and who brought innumerable other babies into the world. I love hearing another side of history like this (though I admit, I knew little about Italian immigration from traditional sources, either.)

These women could be snapped off the tree like the walnut branches, and soon no one would know they existed.

The themes in this book reminded me of a lecture I attended by CanLit superstar Esi Edugyan. She spoke about her experience as a Canadian going “home” to Ghana, though she’d never lived in Ghana, and how her expectations about finding a place to belong were not quite satisfied – she was still an outsider, just in a different way. Kluthe goes though a similar journey as she visits Italy in a bid to understand her ancestor Rosina, to tie together the snippets and whispers she’s heard over the years. Of course, it’s not as easy as getting on a plane. Kluthe’s relatives speak Italian and even with a translator, you get a sense that she’s removed from the real conversation. I had trouble keeping all the relatives straight at times for the same reason – we’re kept at arm’s length.

There’s an air of mystery and secretiveness surrounding Rosina. Some of the relatives aren’t willing to speak. There were difficulties locating her grave. She always seems a few steps out of reach. The silence and shame surrounding Rosina are reflected in the author’s experience with an unplanned pregancy.

I imagined secrets swirling around the burgundy-stained glass. I felt like this secret was a serious one, and I knew I couldn’t ask any more questions

The writing has been described as lyrical, but it’s also really understated and simple, which worked well. Kluthe does a great job tying together the different time periods and settings, and the straightforward memoir with the imagined day-to-day life of Rosina.

Kluthe eventually makes some important discoveries about Rosina, but I wondered how much resolution she felt. This is real life, so it’s not all tied up in a neat little package. I found myself kind of bereft at the end, wondering, now that she knows about her ancestors, her home, how does that play out in her life? Does it help her move on from her loss? Well, a cool thing about reading non-fiction is that Kluthe is a real person so there’s a chance we’ll find out.

I’ve talked a bit about how this book hit home for me. I’ll leave you with this description of that time between thinking and knowing you are pregnant. That stillness and inertia is just how I remember it, too.

The snow stopped. What had fallen had hardened into one crisp layer across the ground. I knew I had to go tot the doctor; it had been almost three months since I had had a period. I had to drive down the highway and into the city to the clinic. I had to pass by the familiar houses, fields, and farms, curve under the overpass and pass the golf course, and wonder if, on my way back, this world would look different. I had already imagined the trip several times, switching between possible outcomes, possible feelings. If I told Mom, she would make me go to the doctor. If I told Karl, we would go together. He’d sit there with me and wait. On the way, he’d adjust the mirrors, the fans. Reset the trip dial.

Thank you to LitFest for the book! Come see Jessica Kluthe this October at LitFest events Writing in Blood (I’ll be there!) and the Writers’ Cabaret for Literacy.

Visit Jessica Kluthe at her website or on Twitter.

The Insistent Garden by Rosie Chard

The Insistent Garden by Rosie Chard | Published in 2013 by NeWest Press | Paperback: 355 pages | Source: Advance reader copy from publisher

My rating: 3.5/5 stars

Synopsis:

Edith Stoker’s father is building a wall in their backyard. A very, very high wall–a brick bulwark in his obsessive war against their hated neighbour Edward Black.

It is 1969, and far away, preparations are being made for man to walk upon the moon. Meanwhile, in the Stokers’ shabby home in the East Midlands, Edith remains a virtual prisoner, with occasional visits from her grotesque and demanding Aunt Vivian serving as the only break in the routine.

But when shy, sheltered Edith begins to quietly cultivate a garden in the shadow of her father’s wall, she sets in motion events that might gain her independence… and bring her face to face with the mysterious Edward Black.

The Insistent Garden is, at first glance, a quiet, contained book, but it contains so much: Coming of age, sexual awakening, mental illness, poetry, and family secrets. Grab a blanket and a cup of tea – it’s a perfect read for the colder days ahead.

Edith’s life stalled when high school ended, and she lives in a household that seems to have stalled sometime in the 1940s – no TV, no washing machine, homemade clothes. While her friends move on to college, Edith is stuck at home caring for her father, who is obsessed with his next-door neighbour and spends all of his free time building a wall between their backyards. Her father’s sister is an evil-stepmother character who ruins at least one of Edith’s days each week with her overnight visits. Her father reads about the moon landing in the paper; the outside world may as well be the moon to Edith.

Edith is not literally stuck in the house. The door isn’t locked. She’s held back by fear: ostensibly of what might happen if her father were left to his own devices, but also of what might happen to her. This is all she knows and she’s been taught to fear outsiders.

Chard talks about the claustrophobia of the story in an interview (listen here) but I didn’t feel stifled. The story begins just as the cracks in Edith’s life are starting to show. She only needs to wander a few blocks from home before she starts bumping into a strange group of characters who work together in mysterious ways to reveal the truth about Edith’s long-dead mother, about her father’s obsession, and about her neighbour, Edward Black. Edith’s awakening takes place as the garden she plants in the shadow of her father’s wall takes root. Continue reading