Tagged: International Booker Prize 2025

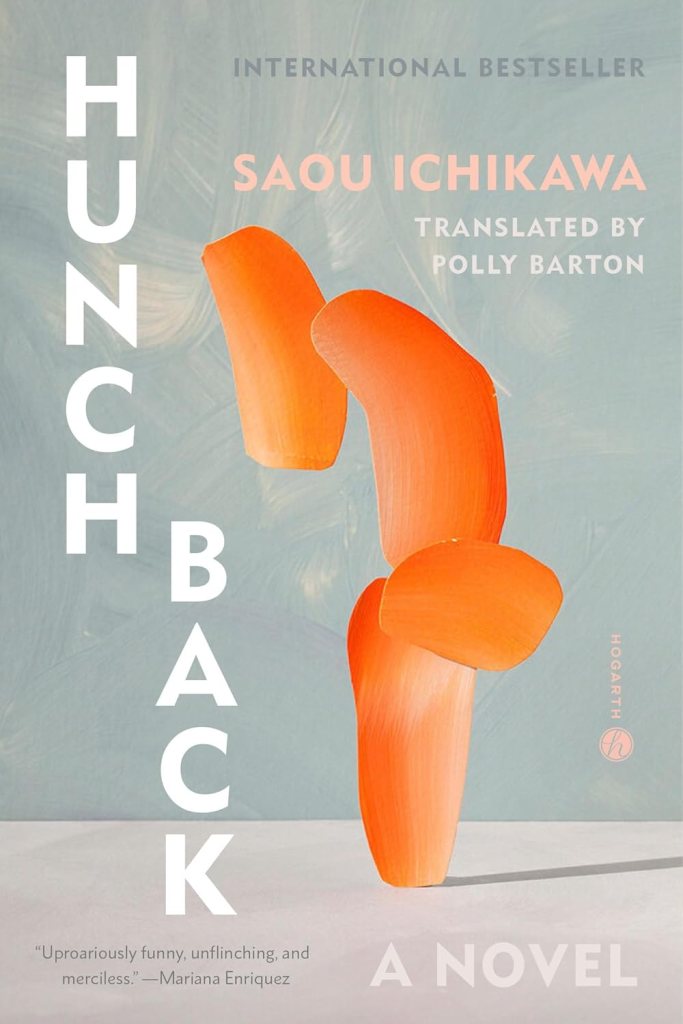

Hunchback by Saou Ichikawa, translated by Polly Barton

In keeping with the spirit of this book, I will be brief.

Shaka is a wealthy middle aged woman with disabilities who lives in an assisted care facility. She says the following about holding a heavy book:

Holding in both hands an open book three or four centimetres in thickness took a greater toll on my back than any other activity. Being able to see; being able to hold a book; being able to turn its pages; being able to maintain a reading posture; being able to go to a bookshop to buy a book—I loathed the exclusionary machismo of book culture that demanded that its participants meet these five criteria of able-bodiedness. I loathed, too, the ignorant arrogance of all those self-professed book-lovers so oblivious to their privilege.

I found it ironic that many reviewers criticize the book for being too short, with underdeveloped characters and plot. To be fair, Hunchback is extra short, stretched over 90 pages in my edition due to wide margins and small pages. But I thought it was clever to have the form follow the spirit of Shaka’s complaint.

Ichikawa packs a ton into those pages – a frame narrative, excerpts from Shaka’s erotic fiction and tweets, literary allusions, some Covid commentary, and yes, a plot – a pretty shocking one!

The frame narrative stars Mikio, a persona Shaka uses to write erotic fiction, which we get to sample in the first few pages. At the end of the book, Mikio reappears and upends everything, in a way that I of course cannot describe here.

Shaka’s story, within this frame, is encapsulated in this anonymous tweet:

My ultimate dream is to get pregnant and have an abortion, just like a normal woman.

Shaka’s not serious at first – it’s more of a provocative commentary on rights for people with disabilities. But when she starts to act on this impulse, Hunchback becomes a story about class as well as disability. She finds a poor “beta male” who works in the assisted living facility to make her dream into reality.

And here’s where I had a little trouble. The scenario is a little far-fetched. The author has said that about 30 percent of Hunchback is based on her life. She asks the reader to believe a lot of convenient things, presumably the fictional 70 percent, to drive the plot and give it symbolic weight.

What ensues is a very twisted Normal People scenario in which a rich girl alternately wants to submit to, and assert her power over, a poor boy who is sort of her employee (this boy is no Connell though, alas). If Ichikawa appeased the critics and developed the story further into the future, or delved into Shaka’s past, it could have become even more artificial. As it stands, the somewhat-convenient plot is balanced by the strength of the writing and the astonishing ending.

The International Booker Prize jury found something compelling in short narratives this year. With the exception of Solenoid, each longisted book is under 300 pages, and most are under 200. Hunchback is not underdeveloped at all. The length works, thematically and structurally.

If I have a criticism, it’s that the narrator’s erotica and shitposts are pretty tame, and I’m not sure if that was intentional or not. But that might say more about my reading and scrolling habits than anything!

On the Calculation of Volume I by Solvej Balle, translated by Barbara Haveland

On the Calculation of Volume I is a compelling read, which is impressive, given that very little happens, and the end of the book is not the end of the story. It’s the beginning of a planned septology, and the last two or three books haven’t even been written yet.

Like The Unworthy, this is a novel written as a diary of a woman who is going through something strange, but unlike The Unworthy, that point of view is perfectly executed. You get the sense that the author has a bigger purpose, a structure that isn’t obvious yet, that needs to be played out in seven parts. I hope it’ll come together just like the calculation of volume came to Archimedes. Just know that there is no “Eureka!” moment in this first book.

Before we talk about what this narrator is going through, I recommend you read this review, in The Cut of all places, which provides some important background on how this book came to be. If you are, like me, annoyed by ambiguous timelines and convenient ways of circumventing technology, it’s helpful to know that Solvej “conceived of On the Calculation’s concept in 1987, then started writing in 1999.” I learned this after finishing the novel, and was instantly less annoyed by the fact that the narrator doesn’t try to use technology to figure out what’s happening to her. If there ever was a time to google “[problem] + reddit”, this is it…

The problem is that, as the story opens, Tara Selter has been living the same day, November 18th, over and over again, 121 times and counting, while the rest of the world is seemingly reset overnight and experiencing a normal, one-and-done day. Her diary takes us back to the first November 18th, the one that was preceded by November 17th, then through some of the intervening 120 November 18ths, and then forward through an entire year of them, without making the diary device feel forced or artificial.

Most of the book is given over to the practical problems of existing out of time, of which there are many. How many times can Tara explain her problem to her husband in the morning, get his help and advice through the day, just to wake up and have to explain it all over again? How long can she hide out in her own house, or other houses, to avoid him when it becomes clear that he’s holding her back? How much food can she eat before the empty cupboards in the house, and then the store shelves in town, are noted? How closely can she observe the world for deviations in how the day unfolds, whether in the movement of stars, or the way a person in a Paris hotel drops a piece of bread at the same time every day, and will those deviations lead her to a way out of November 18th, and back to the regular passing of time?

The most magical thing this book does is make one wonder who has it worse: Tara, stuck in one day, with no way to have a relationship with anyone or anything that lasts more than 24 hours; or everyone else, moving through their November 18th like automatons, unable to exercise free will or see beyond the ruts they run in. Only Tara can step back and try new routes and new angles, and see the possibilities that exist in one day.

One missing element did annoy me though. I kept wondering whether or not Tara gets periods or if she could get pregnant. Hubby’s always willing, no matter what iteration of November 18th we’re in or how far they get in their time travel investigations, and no birth control is mentioned. Other bodily functions seem to move forward, even though the days don’t. Nothing snaps a woman in line with time and seasons and cycles more than all that. But in addition to not knowing what year it is, we also don’t know how old Tara is, so I don’t really know how much of a factor this could be.

I guess we have six more books in which to figure that out, along with more pressing questions like why did this happen to Tara and how can she break free? I look forward to shouting “Eureka!” in a few years, once those last books are written and translated into English – assuming I don’t fall into a time warp before then.