Tagged: drumheller

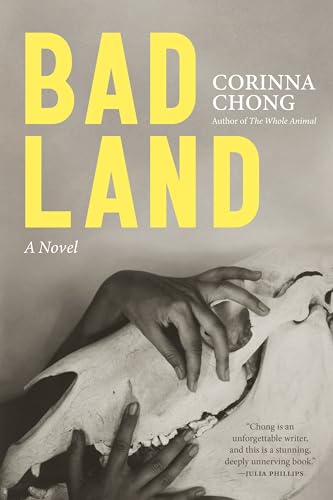

Bad Land by Corinna Chong

I don’t love the mountains, which is a controversial thing to say here in Alberta. Everyone goes to the mountains, and feels at peace, at home, in awe, or whatever. Many “leave their heart” there. Maybe it’s because I grew up in Vancouver, where it was normal to see mountains (and an ocean) but I need a little more than a large rock formation to get me speaking in clichés.

I’m also not easily impressed by so-called disaster woman stories. There’s got to be a little more going on than “this woman is weird and messy.”

Bad Land, thankfully, has got more going for it. In addition to a weird woman, there is also a weird little girl. And it’s not set in the mountains; it’s set in the one place in Alberta that actually does make me feel a sense of awe: the badlands.

“Then the puckered hills begin to swell out of the earth, growing higher, wider, baring their stripes of ancient rock and clay and ash, layer upon layer. As the Buick sinks into the valley, the hills knit together behind them, closing them in.”

That’s exactly how I feel driving into Drumheller. The landscape is not just majestic and imposing, it’s downright alien. It also contains a ton of fossils and other buried treasures, enough to capture any child’s imagination.

Growing up there makes it a little less magical. Regina’s Drumheller childhood with her younger brother Ricky and German paleontologist mother, called “Mutti,” feels as stifling as you might expect. The book opens with adult Regina still there, living alone in her childhood home, estranged from her family, and working at the most stereotypically Drumheller place possible. She’s a character, known for taking her beloved bunny, Waldo, for walks around the neighbourhood, and for her imposing size. Regina is surprised to find Ricky on her doorstep after seven years of no contact, with a six-year-old daughter, Jez, in tow. The rest of the novel unravels the reasons for the estrangement, and tracks Regina’s bond with troubled Jez and her efforts to find and reconcile with Mutti.

A flashback illustrates Regina’s strained relationship with her mother. Young Regina tries to impress her mother by finding treasures in the badlands, thinking that Mutti would “gasp, praise my keen eye, and offer to take me out for ice cream” if she could just find a fossil, or a piece of amber. Regina eventually finds what she imagines is a dinosaur egg. When she breaks it open with a hammer and finds something even more magical – sparkling crystals – she imagines Mutti will “jump out of her stockings” and that they will be famous for their discovery. Of course, it’s just a geode, and Mutti is quick to tell her it’s nothing special, at least not anymore.

“It might have been worth something, you know. I think about four hundred dollars, maybe more. But there you’ve gone, smashing it to bits. Must you go around smashing everything, Regina?”

Chong has dug into strained mother-daughter relationships before, in her debut novel Belinda’s Rings. Both novels feature distant mothers with the kind of STEM jobs that little girls dream about (a marine biologist in Belinda’s Rings), absent fathers, fraught sibling relationships, and generational trauma and abuse. Sudden outbursts of violence feature in both books. The past is always just below the surface, threatening to break through. Bad Land is a more mature work, and takes more risks. It can be read as a thriller, full of twists and family secrets, culminating in a madcap road trip. Or, it can be read as an examination of one woman’s inner life, rich in metaphor and atmosphere, and mysterious in its conclusions about family and memory.

Maddeningly for such a propulsive read, Chong makes some choices that throw the reader out of the story. The most jarring was Regina’s analog lifestyle – no phone, no computer, and as far as we’re told, no media consumption at all. I was compelled to hunt for clues about her age and the year, hoping to justify this choice as something other than a plot contrivance – as with most fiction, it’s very helpful when characters can’t Google things- but Bad Land is mostly devoid of political and pop culture references. I eventually found enough to place the present-day narrative in 2016, and peg Regina at 36, which makes Regina’s inability to conduct a simple Google search strain credulity.

I flew through Bad Land, but upon finishing, I wasn’t sure how I felt, or how successful the novel was. So, I sought out reviews. Surely, a Giller Prize-nominated novel that was published mere weeks ago would have a couple of reviews to peruse. Other than an unfairly negative review in Publisher’s Weekly (which refers to Randy’s wife as Clara rather than Carla) and a positive review in a BC literary journal (which refers to Waldo as a childhood pet; he’s definitely not) there’s very little to go on. There are ten reviews on Goodreads, one of which is mine. This probably says more about the state of review culture than the book, but I was sorely disappointed!

Despite my uncertainty, I hope more people read Bad Land, mostly so I can read more perspectives on it. I want to know whether you think Regina’s character is supposed to reflect how childhood trauma becomes an adult fear of abandonment, and that her bond with Jez shows how trauma can be healed by the love of a child. Or, as I tend to think, that Regina is the “bunny lady” and Jez is lost in a dream world for reasons that aren’t so simple, or maybe for no reason at all.

Like a fossil is only an impression of the real thing, all we can know of Regina is what Chong shows us. Bad Land is haunting no matter which way you read it – and like a geode, whether you break it open the right way or not, it’s still beautiful.